Theme and Theme and Variations

Blue Prince and the art of repetition

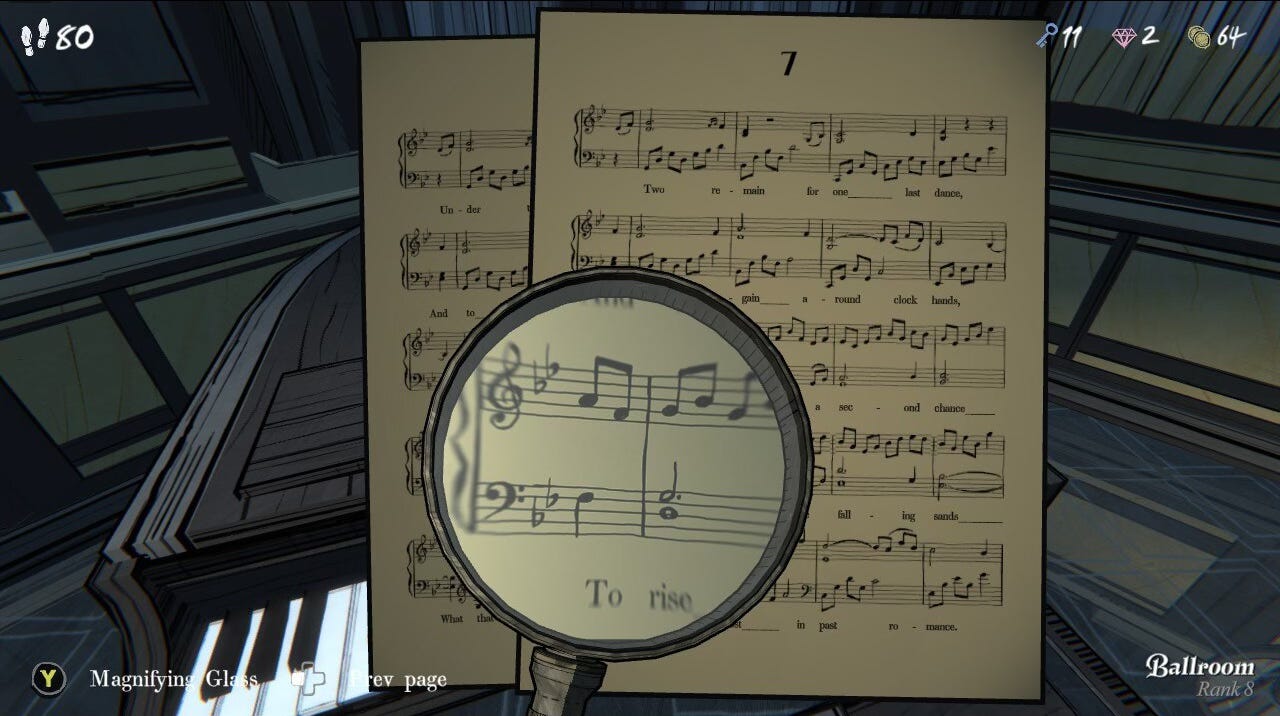

For the past month I’ve been enraptured by Blue Prince, a new video game about exploring a mysterious, ever-changing mansion. I cannot overstate how well-made it is, and how deeply it has bewitched me.

Over the dozens of hours I’ve spent playing, I’ve been impressed by its grasp of tone, design, narrative, and pacing, but I’ve been equally fascinated by its embrace of repetition. That, in turn, has helped me understand some things about the role repetition can play in artistic expression, and in my own creative life. It’s probably not a coincidence that music and video games, two art forms that occupy so much of my time, are also two that so readily employ repetition.

Not all art forms lend themselves to overt repetition, after all. Films tend to move from scene to scene without pausing to revisit or replay what’s come before. (Deliberately repetitive films like Groundhog Day, so often compared with video games, are the exception.) A painting or a photograph may only convey a single image; a novel a single, linear story. Many puzzle games, too, present the player with a series of non-repeating challenges, each of which must be unlocked in order to move on to the next one. The puzzles get more and more complex, building on new mechanics as they’re introduced, but the progression is more or less straightforward.

Blue Prince steps away from that more linear approach by embracing the repetitive structure of what’s known as a roguelike. A central feature of roguelike games is that every so often, usually after an in-game death or other fail-state, the game resets. Players must start over from the beginning, armed only with whatever skill and knowledge they gained on the last run, and perhaps one or two small, hard-won permanent upgrades. Roguelikes commonly focus on combat or strategy gameplay, rather than puzzle solving, but in recent years, a few puzzle games—Outer Wilds, Inscryption—have embraced repetitive run-based design with smashing results.

In Blue Prince, the player character’s great-uncle, a wealthy and enigmatic puzzle-lover, has died and left his nephew the equally enigmatic family estate. There’s a caveat, however: the inheritance will only take effect if the nephew can reach the seemingly unreachable 46th room atop the manor’s 45-room floor plan.

Each in-game day, players are presented with an empty 9x5 grid, and must draw up a new layout for the house. They do so by exploring the rooms in first-person, then choosing one of three randomly-chosen blueprints at every closed door. There’s a fair bit of strategy involved in choosing how to move through the house and where to place rooms, but as the day’s floor plan solidifies, the player’s focus shifts to solving puzzles. A given room will hold both self-contained puzzles (how do I open the safe in the Drawing Room?) and subtle clues to larger, estate-wide mysteries (why are there different chess pieces on the shelves?). Solve enough of the latter, and the mansion’s backstory begins to emerge, an unusually engrossing tale of family, politics, and revolution that I’m still in the process of unspooling.

No matter how well you may do on a given day, your character will eventually run out of energy or find himself otherwise unable to progress. At that point the day ends, and a new one begins with a fresh grid, and 45 new possibilities for mystery and learning. That seemingly simple idea—a mercurial mansion that resets itself each time the player goes to sleep—is the key to the game’s repetitive, nonlinear flow, and to the stickiness that makes it so engrossing and satisfying.

At the 2011 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, game designer Clint Hocking gave a talk called “Dynamics: The State of the Art.” In it, he made a convincing argument for dynamics as the primary means through which games generate meaning. Dynamics here referring to change, so: games find meaning through their ability to change in response to the player. “This is the art,” he said, “of showing your audience that they are in fact artists themselves.”

I attended the talk and loved it, both for the ideas he was presenting and for the fact that a person could even try to nail down the single element by which a given art form generates its most distinct meaning. What a thing to attempt! It made me want to identify other secondary elements that might play a similar, if less primary, role.

One of those is repetition, an element that has featured heavily in a number of my favorite games from the past few years. Repetition has an interesting relationship to Hocking’s dynamics. Certainly, it plays an outsized role in most video games—try, die, reload, and so on. And at a first glance, repetition seems antithetical to dynamism. How can something that keeps repeating also be dynamic?

But of course, if you’ve played a video game, you know that repetition often enhances dynamism, rather than smothering it. You may fight a difficult boss thirty times, but on that thirty-first time, when you finally get him, your victory is all the sweeter. Similarly, you may spend ten minutes staring at the same series of locked doors, but by the time you work out the way forward, you will know those doors better than some in your own home. In both cases, that repetitive period of stuckness not only enhanced the thrill of your eventual success, it was also necessary to develop the skills or knowledge required to succeed at all.

Repetition is also essential in music, and in the work of being a musician. Most basically, there’s the fact that musical mastery is built on a foundation of repetition in the practice room. But musical composition, too, routinely uses repetition to generate meaning—repeated motifs, melodies, loops, samples, and even whole sections of compositions, with a complex series of notation elements (repeat, first and second ending, D.C., D.S. al coda, etc.) designed to communicate specific types of repetition. “Play 2X only” reads a scrawl on the violin part, indicating that the strings are only to enter on the second time through a given section. When they do come in, they’ll add a layer of complexity to something the audience has already heard once.

That productive tension between repetition and dynamism is also at the heart of musical theme and variations. You have to establish a theme in order to vary it, and in order to establish a theme, you gotta play it a few times. When John Williams sneaks a minor key version of the Star Wars theme into Empire Strikes Back, we’ve heard the original enough times to understand what the moodier rendition might imply. When Sonny Rollins blows on “St. Thomas,” he starts not with his longest lines, but with his simplest, most repeatable ideas. And as every blues musician knows, you haven’t really asked a question until you’ve asked it a second time over the four chord.

Blue Prince embraces repetition to ingenious ends, enticing the player into a labyrinth of mystery and revelation that unfolds according to the long, pulsing rhythms of an extended symphony. I play and play until I hit a new D.C., each time hoping that I might unlock a coveted D.S. al coda. (And when, I wonder, might I finally reach that elusive fine?) Again and again I stack these chords and melodies, each time in slightly different formations, until I’ve learned to anticipate each new chime of harmony, or scrape of dissonance, before it has sounded.

With every new day, the orchestra and I re-express ourselves. Rarely have I felt so alive inside someone else’s composition.

Exoskeletal Judgment at the Railroad, Delayed

Repetition is an essential part of creating music, but it’s often just as important when it comes to listening to it. The newest episode of Strong Songs focuses on a song that took me quite a few repetitions before I could get on its level: “Roulette Dares (The Haunt Of),” by The Mars Volta, from their 2003 psych-prog masterpiece De-Loused in the Comatorium.

I recount my relationship with De-Loused in the episode, but it bears consideration in the context of the essay above, as well. Musical composition may lend itself to repetition, but it engenders repetition in its audience, as well. That makes sense, since all art reproduces itself in its audience, to some extent. But I have listened to my favorite albums far more times than I’ve read my favorite novels or watched my favorite movies, and the recursive repetitions of a given musical work only grow in my mind with each subsequent listen. It’s just spirals, within spirals, within spirals.

With De-Loused, what began as a challenge to myself—can I get over the hump with this abrasive, challenging album, and decipher the greatness within it?—eventually, with repetition, became a comforting relationship with a familiar friend. I’ve probably listened to it more than a hundred times, and each time through I hear something new.

The process of making the episode involved several similarly rich re-listens; if anything, the process was enhanced by stopping to learn Omar Rodríguez-López’s guitar parts and Jon Theodore’s recursive drum patterns. That experience was further enhanced by my parallel viewing of Omar and Cedric: If This Ever Gets Weird, an unexpectedly lovely documentary that I really can’t recommend enough.

I hope you all enjoy the episode! I know it’s a more challenging style of music than a lot of what I cover on the show, but I hope that won’t scare too many of you off. As with so much great art, De-Loused in the Comatorium gives back what you put into it and then some.

Loose Links

On Triple Click: last week we talked about the just-announced Nintendo Switch 2, and this week’s ep was all about Blue Prince

Also, Triple Click is doing a live show in Portland this July! It’s on Friday, July 11, and it’s gonna be awesome and you should come

Speaking of Blue Prince, my buddy Stephen Totilo at Game File published a cool interview with the game’s lead creator Tonda Ross earlier this year

I also liked Christian Donlan’s review at Eurogamer

José Vadi’s lovely LARB tribute to Mars Volta keyboardist Ikey Owens that I didn’t have time to mention on the Mars Volta episode

An inspiring Guardian interview with Jeff Bridges about his life as a musician, and his relationship to songwriting

We Want The Funk, Stanley Nelson and Nicole London’s fun new music doc feat. some funny bass stories

A good video about the spread of online gambling that pairs well with this other good video about the increasing popularity of gacha games

RIP Clem Burke, the heartbeat of Blondie

A rare interview with Tracy Chapman in the Times to go with the re-release of her self-titled 1988 debut

Onward

That’s enough for now; I’ll try to have some music recommendations to share next time around. As always, you can find me doing my thing on Instagram and Bluesky, by which I mean not logging in or posting very much.

I’ll leave you with this pic of Cooper, Emily’s folks’ new puppy, who is still learning how to sleep in his bed properly. We trust he’ll get there eventually.

Take care, and keep listening -

~KH

4/10/2025